Dr. Faris Almushrafi, Dean of the Department of History at King Saud University, said National Day is not just a day to remember events or celebrate beginnings, but also an opportunity to examine the very means by which a nation defines and asserts itself.

The most important of these is the seal, a compact documentary document that distills the concept of a nation into a single stamp.

Al-Mushraf told Asharq Al-Awsat that since a seal cannot be read apart from its political and administrative context, examining its structure and formation opens the door to a deeper understanding of the nature of the state that produced it.

A seal attributed to Imam Saud bin Abdulaziz (1229 AH/1814), the third imam of the First Saudi State, was used to authenticate official correspondence, such as letters to the governor of Damascus, during the first decade of the 13th century AH.

The seal has the inscription “His Servant Saud bin Abdulaziz” in the center and the date 1223 AD in a circular frame that suggests integrity and order.

According to him, seals are not made for decoration, but for official recognition. Its existence indicates a central authority whose decisions and communications need to be documented, and a representative-minded administration. Every envelope implicitly declares, “This is a nation where a nation speaks in its own name.” Legitimacy does not come from the content alone, but from the stamps placed on it.

Colonel Al-Mushraf said that the expression “His servant Saud” has transcended the personal dimension and entered the language of political correctness. The choice of the word “servant” reflects the concept of authority, inseparable from religious references, and leadership is presented as a moral obligation before it is a political privilege.

He says the language is not voluntary, but represents a model of governance that sees political power as incomplete without value-based legitimacy, and that sees the state as operating within, rather than on, a belief system.

Seal and condition features: inside and outside

The head of the Department of History at King Saud University emphasized that the seal’s importance is even greater given that it was used in communications beyond the local territory addressed to the Damascus governor.

In this context, the seal became an instrument of external political relations, reflecting the consciousness of the Saudi first state as a political entity that communicated and defined itself in the formal language recognized in the world of political communication at the time. Therefore, the seal was not only directed inward, but also performed a sovereign function without.

At the same time, the inclusion of the Hijri date on the seal is not just a formal detail, but an indication of the chronological order of administrative operations.

He said countries that date documents understand the importance of order, priority and evidence, and recognize that political action is incomplete if it is not corrected in time. Here, the early features of what can be called the administrative spirit of the first Saudi state begin to emerge.

Al-Mushraf said that placing the seal in its modern regional context and comparing it with the seals of other Islamic states from the late 18th and early 19th centuries makes its significance clearer.

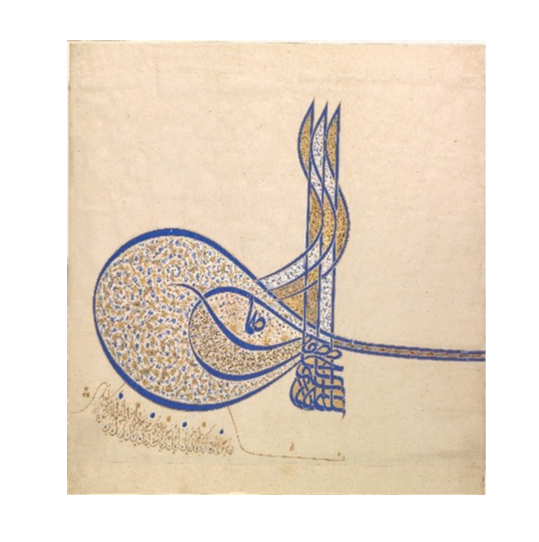

In the Ottoman Empire, the imperial tugra served as a composite sovereign signature, inscribing the sultan’s name and title in an elaborate visual format.

It had a highly symbolic function emphasizing imperial class and hierarchical authority beyond its procedural dimension, turning the seal into a visual declaration of sovereignty as well as a tool of authentication.

In Qajar Iran, the official seal was similarly tied to the shah’s name and title, clearly emphasizing personal seals and the legitimacy of the king, making the seal more than a neutral administrative instrument, but an extension of the ruler’s prestige and a symbolic expression of the state.

In Egypt under Muhammad Ali Pasha, despite early features of administrative modernization, the official seal continued to function within the language of authority and status derived not only from its text but also from the sovereign structure to which the ruler belonged as governor of the Ottoman Empire.

Even when Muhammad Ali used the expression “His servant Muhammad Ali,” it did not function as a fundamental definition of legitimacy, but rather as a procedural courtesy within Ottoman writing conventions, and a distinction of rank within the seal. While softening the mood, official titles were restored outside the seal through a system of official ranks and designations, including high-ranking “pasha” and “governor of Egypt” in the Ottoman administrative and military hierarchy, al-Mushraf said. the formulation of legally and sovereignly recognized titles and protocols such as “Protected Governor-General of Egypt”;

In the case of Egypt, the seal was both a written instrument and a declaration of a political position, inseparable from the higher authority structure that defined the ruler’s position.

In contrast, the Saudi seal shows a different wording, al-Mushraf said. The phrase “His Servant, Saud bin Abdulaziz”, in combination with the Hijri date, is sufficient to serve as official recognition and administrative recognition, without any symbolic designation or exaggeration of the title, or any reference to a higher sovereignty outside the framework of the state itself.

Here, the seal’s function as an instrument of state takes precedence over its role as an expression of class, reflecting a model of sovereignty based on economy of symbols, clarity of expression, and administrative discipline. This distinction, he said, is important for understanding the nature of the first Saudi state and the logic of its initial formation as a state that defines itself not only through the grandeur of its symbols but also through its functions and practices.

Seals and functions of the emerging Saudi state

In light of this regional comparison, Colonel Al-Mushraf said that Imam Saud bin Abdulaziz’s seal should not be interpreted as an isolated administrative tool, but should be understood in the context of the then-emerging Saudi state.

It was established not as a ritual or symbolic entity, but as an authority concerned with regulating, enforcing rulings, securing territory, and organizing internal and external relations.

In this context, the seal becomes a direct reflection of the functioning of the state, becoming a tool for approving decisions, amending communications, and regulating political behavior within a clear legal framework.

The simplicity of the wording on the seal, the economy of the title, and its association with hijra all indicate that the state views authority as a responsible practice prior to any display of sovereignty. He said a state with minimal symbols prioritizes action over rhetoric, organization over decoration, and function over expression.

The seal is therefore read not as a sign of the imam’s person, but as an instrument of the state that functions, communicates, binds, and records.

In this sense, the seal of Imam Saud bin Abdulaziz is a testament to the nature of the primary Saudi state as a practicing state, defining itself by what it does rather than what it shows, and confirming its existence not only through symbolic grandeur but also through administrative and legal discipline.

Almushraf concluded that the seal teaches that a nation is read not only in its battles and major treaties, but also in its silent details: its seals, signatures, and linguistic formulations.

Remembering this seal on National Day is not just a celebration of an ancient relic, but also a conscious reading of the moments that shaped the Saudi state as an entity with a sense of legitimacy and political representation.

In this way, the seal becomes a historical witness that declares: “Here is a nation, here is an authority that knows itself and knows how to assert its presence.”