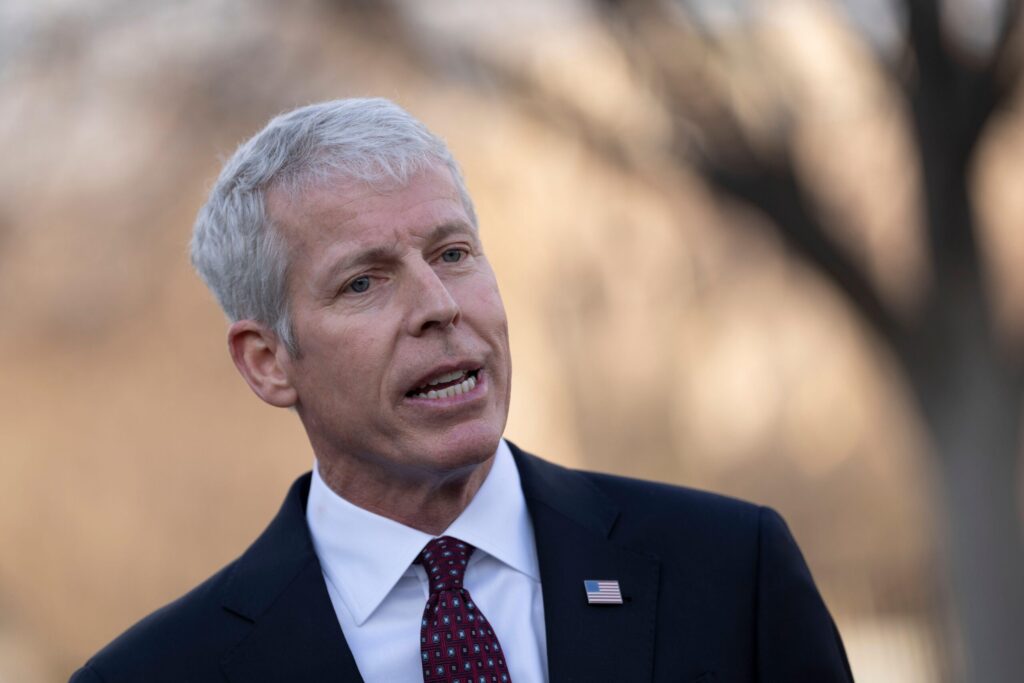

US energy secretary Chris Wright is in the Arabian Gulf to reaffirm America’s commitment to the region, where he has signed deals and MoUs with policymakers in Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Qatar.

But despite President Trump’s “Liberation Day” and the outbreak of open trade hostilities between the US and China, Gulf energy leaders are quietly getting on with the role they have fulfilled for the past three decades: fuelling the Chinese economy.

Saudi Aramco’s decision to supply crude at record low prices to China and other Asian markets is proof of that.

The Arabian Gulf has long walked a diplomatic tightrope between the US and China with some skill.

Courting Beijing’s markets while relying on Washington’s firepower, Gulf capitals have grown used to performing a balancing act which requires strategic ambiguity, patient diplomacy, and commercial pragmatism.

Trump’s tariff-driven trade war threatens to shake that equilibrium. His economic nationalism is fast becoming a tool of confrontation, not competition – and it is forcing the rest of the world to reassess old assumptions.

For Gulf policymakers, who have hitherto resisted the binary choices the US-China rivalry is forcing on the world, the pressure to choose is mounting. The decision, if and when it comes, will not be ideological. It will be made – as it always is in this hydrocarbon-rich region – through the prism of energy.

Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Qatar have the capacity to influence the global energy system via their vast supplies of oil and gas. The challenge now is how to use that leverage without becoming collateral damage in someone else’s economic war.

China’s appeal is clear. It is the world’s largest oil importer, with Gulf crude flowing into its ports in decisive volumes. While the US has become a net energy exporter, China remains structurally dependent on hydrocarbon imports.

It is also advancing its energy transition on its own terms, blending renewables with abundant coal and increasing demand for natural gas and petrochemicals. From a Gulf perspective, China is a long-term and reliable customer.

But the US still matters hugely, especially in the Trump era. It remains the Gulf’s principal security provider, its most sophisticated source of technology (as we saw in Washington’s deal to approve a nuclear deal – finally – with Riyadh last weekend), and a crucial partner in capital markets.

In energy, American companies play a major role in upstream investment, carbon management, and the development of future fuels. The Gulf’s clean hydrogen ambitions, for instance, depend in part on access to Western science and financing.

This creates a paradox. The Gulf’s future wealth may depend more on globalist China than protectionist America but its ability to realise that wealth runs through Washington – at least into the medium term.

Some in Riyadh and Abu Dhabi argue that the region’s best play is to stay exactly where it is: friendly to both, beholden to neither.

This is easier said than done. Trump’s tariffs will not only affect trade flows; they will increasingly shape geopolitical alignments. There could come a time when Gulf “neutrality” is no longer an option.

Energy diplomacy offers a path forward. Rather than framing oil and gas exports in transactional terms, Gulf states can use them as tools of influence and reassurance – deepening China’s dependency in ways that generate leverage and reinforce the enormous trade in non-oil products and services.

Washington meanwhile would retain continued influence over global strategic reserves, ongoing capital flows between the US and the Gulf, and – importantly – a voice in global pricing mechanisms like Opec+, even if from the sidelines

In this way, Gulf energy becomes not just a commodity, but a currency of geopolitical relevance. It allows the Gulf to remain indispensable – not just as the global swing producing region, but as an orchestrator of global energy strategy.

This plan has risks. It requires diplomatic finesse, and the institutional maturity to build simultaneous trust in two very different capitals. It also demands that Gulf states remain internally strong enough to see through the “vision” strategies of diversification they are all pursuing.

It is too early to bet on a “winner” in the US-China race, but in any case the perils of getting it wrong make that an unwise choice. Better to play for time – and use energy diplomacy as the main gambit.

There may come a time when the region has to choose – for example in the currency for pricing crude oil barrels, or the creation of new financial payment systems, or even the advantages of the dollar peg regional currencies enjoy.

But for the next four years at least, it would be wise to continue to ride two horses.

Frank Kane is Editor-at-Large of AGBI and an award-winning business journalist. He acts as a consultant to the Ministry of Energy of Saudi Arabia

Register now: It’s easy and free

AGBI registered members can access even more of our unique analysis and perspective on business and economics in the Middle East.

Why sign uP

Exclusive weekly email from our editor-in-chief

Personalised weekly emails for your preferred industry sectors

Read and download our insight packed white papers

Access to our mobile app

Prioritised access to live events

Already registered? Sign in

I’ll register later